In 1997 Labor Party chairman Ehud Barak asked Mizrahi Jews to forgive the party for its treatment of the 1950s North African immigration. He got the idea from Daniel Ben-Simon’s book Another Country which tells the story of Benjamin Netanyahu’s 1996 victory. Ben Simon recalled a conversation between Shimon Peres and Shas’ leader, Aryeh Deri. Dari told Peres that “The Moroccans don’t like you. They don’t forgive the Labor Movement for its treatment of them in the 1950s” and advised him to ask for forgiveness. “Mind you, he told Peres, they are not in the Likud’s pocket. On the contrary. They are moderate and tolerant people.” Barak called Ben Simon the night he decided to apologize. Ben Simon thought it might work

I asked him why Barak’s apology was did not help heal the wound. “Barak wanted to steal the oriental vote from the Likud,” he said, “and he won the election. He won the election because the Orientals voted from him in 1999. He had a huge victory. But after the election he went back to being Barak, the Israeli army general who promised change of priorities and did nothing for it. […] He was busy with the Palestinian issue and eventually those orientals saw him as a person who couldn’t keep to his word.” Ben Simon argues that what had to be done then and still hasn’t been done is “a Marshal Plan for the development towns.”

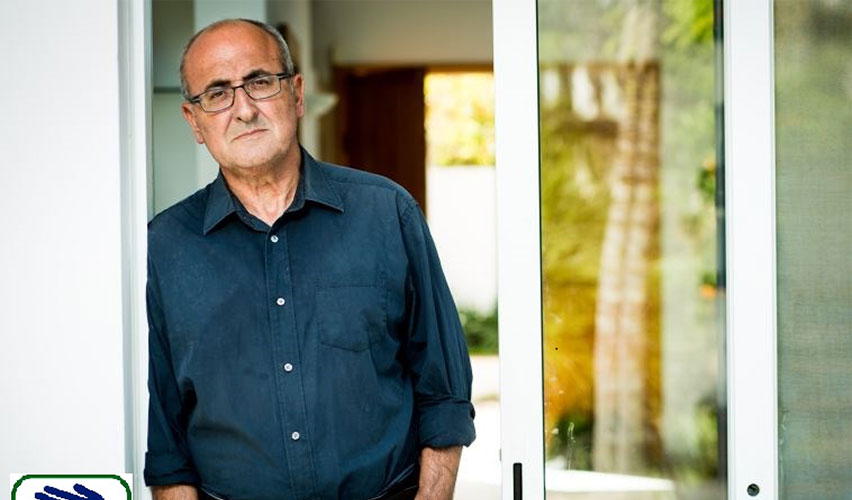

Our interview revolved around Ben-Simon’s new autobiographical book, The Moroccans (currently only in Hebrew). Ben Simon grew up in Casablanca, Morocco and immigrated to Israel with his ten-year-old sister in 1969 is what was called ‘Youth Aliya.’ He studied journalism at Boston University and worked for Davar, the mouthpiece of the Histadrut and Mapai, and later in Haaretz. In 2008, he joined the Labor Party, was elected to the Knesset and served as Labor Party Knesset chair.

I read The Moroccans shortly after it was published in February 2016 and it left a strong impression on me. Ben-Simon describes a uniquely moderate community in Morocco that lived well with its Arab neighbors and maintained a Jewish identity without sacrificing its modern outlook. He tells of renowned rabbis who allowed Jews to drive on Shabbat and go swimming after prayer. He compares Mizrahi traditionalism to Reform American Jews and argues that his community was European, but the interaction with Israelis orientalized them. Suddenly, his neighbor in Casablanca Arieh Deri, whose father did not cover his head, became religiously fanatic. Their hatred to the Israeli Left turned them nationalist and suspicious of Arabs.

In the most powerful part of the interview Ben-Simon describes how his work in the Ashkenazi elite’ tower (Davar, Haaretz and the Labor Party) tore him from his community. Moroccans he met repeatedly asked him to choose sides: “are you with us or with them?” At the same time, his Ashkenazi colleagues who felt comfortable making racist comments in his presence. The legendary editor of Davar, Hanna Zemer, asked him “What’s the deal with the Moroccans? Don’t take it personally, but admit that you are not a typical Moroccan. You are a gentle and cultured person,” before assigning him to write articles explaining why “Moroccans here are so problematic and unaccomplished, while French Moroccans are so successful.”

In 1998, Ori Orr, the IDF general turned Labor Party prince, finished his political career by speaking frankly to Ben-Simon about “the ungratefulness of Mizrahi voters to the Labor Party.” “I’m sad,” Orr told him “that Barak’s apology did not work. […] And to be clear, I don’t blame Ehud, I blame the Mizrahim.” Orr expressed his disappointment that the Mizrahi immigrants of the 1950s had not “gotten over it.” To be sure that Ben Simon would not take it personally, he called him “an intelligent Moroccan. Not like them.”

What Orr and many of his colleagues on the Left fail to see is that while the origin of the rift between the left and the Mizrahi community might have begun in the 1950s, their bias against Mizrahim reproduced the trauma of the 1950s. The wound never healed because Ashkenazi elite leaders like Ori Orr failed to examine their own action.

When I asked him what the left could do to appeal to Mizrahi voters, he said, Meretz and the Labor Party needed to represent the Mizrahi community and change their attitude toward religion. In an interview to Haaertz however he responded to a similar question: “the Party needs a receiver. It is lost.”

Maybe the Labor Party should change to allow Mizrahim to see themselves in it?

Certainly. This is an excellent formula. Replace the people, disassemble, and rebuild everything anew. This is not a cosmetic treatment; this is a surgical operation. Open the chest. Replace the valves. Make the heart throb again. The party has a serious illness. Because, remember that when Amir Peretz was voted Labor Party leader, nine MKs left the Party. This is unforgiveable. And who led the escape? Do you remember? Shimon Peres. […]

OK, but there was the Kadima Party was formed…

“But the Founder of the Party left!”

Do you mean to say that the Founder left when the Mizrahi reached the top?

“Exactly. It’s like the encounter between Moby Dick and Captain Ahab. Precisely at the moment that everyone is waiting for, he jumps into the water and disappeared. […] And at the climax, when Amir Peretz reached the top and spoke Moroccan – they left. This is not a symptom of the disease; this is the disease.”

Ben Simon argues that what had to be done then and still hasn’t been done is “a Marshal Plan for the development towns.”

And THAT requires ending the Occupation and reshaping the country’s priorities. The two struggles are not separate.