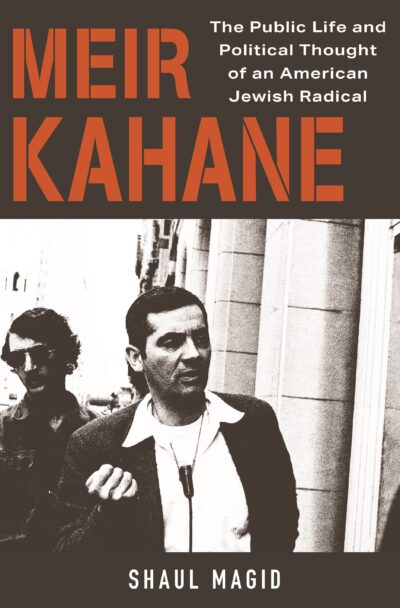

Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical

By Peter Eisenstadt

Like a madeleine dipped in a cup of arsenic, Meir Kahane brings back many memories of things past, especially my adolescent years in the 1960s and early 1970s spent in Rochdale Village in Queens, where Meir Kahane was for a time the rabbi of the Orthodox shul. At the time, Rochdale was the largest housing cooperative in the United States, with almost 6,000 families. Rochdale was a new community, which opened in late 1963. It had been constructed by the United Housing Foundation (UHF), a remarkable organization that under the direction of Abraham Kazan, a veteran of the anarchist wing of the Jewish labor movement, who, in collaboration with the definitely non-anarchist Robert Moses, from the 1950s through the early 1970s, built over 35,000 units of cooperative housing in New York City, culminating in Co-Op City in the Pelham Bay marshes. Rochdale was located in South Jamaica, one of the largest Black communities in the city, and by the late 1960s it was probably about 75–80% white, of whom the vast majority were Jewish families, and the remainder African American. It was one of the few truly integrated neighborhoods in New York City. And for a while, Meir Kahane lived there.

When Kahane took up the bimah in the Orthodox shul, in the fall of 1968, he had, only a few months before, in May, founded the Jewish Defense League (JDL), the organization that would make Kahane famous, adored, and reviled, the self-proclaimed scourge of antisemites and self-hating Jews. (In Kahane’s worldview, everyone, except for his small sliver of the remnant of the righteous, fit into one of those two categories). His reputation as being “to the right of George Wallace” preceded him to Rochdale, and it was during his stay there that Kahane began to earn his enduring notoriety. Within a few months, the orthodox shul, supposedly in an effort to keep his enemies at bay, was adorned with a crown of razor wire, looking more like an auto parts store in a tough neighborhood than a synagogue.

These memories are occasioned by reading Shaul Magid’s important new book, Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical. Magid is absolutely correct that the Jewish left and the Jewish right, each for reasons of its own, have both conspired to minimize the importance of Kahane and of the long, lingering, and ugly shadow he cast on Jewish life on two continents. He was a prophet without much honor, but with many silent admirers. And Magid is absolutely correct that to understand Kahane, you have to see him as an American and New York Jew to his core. He speculates fruitfully on why, after his aliyah in 1971, he never quite fit into the Israeli political scene, perhaps because the county’s leadership didn’t need a loudmouth provocateur to convince most Israelis that they were in a perpetual war against Palestinian nationalism. But in Kahane’s wake, in the US, the “liberal Jewish establishment” became less liberal, as did, to some extent, the American Jewish community as a whole. The JDL’s slogan, “never again,” was a sign that American Jews would become comfortable in invoking the Holocaust at the drop of a hat against their domestic enemies, while, the Nazis notwithstanding, would become more attuned to their potential enemies on the left than on the right, more concerned about Black antisemitism than the frothings of latter-day Aryans. No one can argue, of course, that Kahane was in any way single-handedly responsible for these trends, but there is little doubt he helped give much initial impetus to this general rightward shift.

These memories are occasioned by reading Shaul Magid’s important new book, Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical. Magid is absolutely correct that the Jewish left and the Jewish right, each for reasons of its own, have both conspired to minimize the importance of Kahane and of the long, lingering, and ugly shadow he cast on Jewish life on two continents. He was a prophet without much honor, but with many silent admirers. And Magid is absolutely correct that to understand Kahane, you have to see him as an American and New York Jew to his core. He speculates fruitfully on why, after his aliyah in 1971, he never quite fit into the Israeli political scene, perhaps because the county’s leadership didn’t need a loudmouth provocateur to convince most Israelis that they were in a perpetual war against Palestinian nationalism. But in Kahane’s wake, in the US, the “liberal Jewish establishment” became less liberal, as did, to some extent, the American Jewish community as a whole. The JDL’s slogan, “never again,” was a sign that American Jews would become comfortable in invoking the Holocaust at the drop of a hat against their domestic enemies, while, the Nazis notwithstanding, would become more attuned to their potential enemies on the left than on the right, more concerned about Black antisemitism than the frothings of latter-day Aryans. No one can argue, of course, that Kahane was in any way single-handedly responsible for these trends, but there is little doubt he helped give much initial impetus to this general rightward shift.

That said, Magid’s book was, for this reader, somewhat disappointing. It could have been more clearly and less repetitively organized. Magid is never an easy read, but his analyses of Jewish philosophy, as in his American Post-Judaism, are challenging, extraordinary, and very much worth reading. However, as a historian of New York City, I found him somewhat less surefooted. Two examples: To say that by 1968, Albert Shanker, the president of the United Federal of Teachers (UFT) was “an unlikely target of African American anger” is just wrong. The animosity had been growing for years. And my next objection is a bit pedantic, but Magid repeats it about ten times in the book. No, when the JDL was founded in May 1968, it was not “during the New York City teachers’ strike.” That hundred megaton blast took place that fall.

One of Magid’s central points, present in the title, is that Kahane was a “radical,” that his tactical inspiration was the Black Panthers, and that he shared with Jewish radicals on the left an abhorrence of stand-pat, assimilatory, mainstream Jewish liberalism. There is surely something to this; Kahane was not the only figure on the right with a bad case of Black Panther-envy, with their gun brandishing and headline-generating charismatic newsworthiness. But arguments like Magid’s that emphasize the similarity between the “far left” and the “far right” usually emphasize superficial resemblances rather than deep affinities. To argue, with Magid, that Kahane “was more a child of postwar American radicalism of the left than the maximalist Zionist Revisionism” doesn’t make much sense to me, and after reading Magid, Kahane still strikes me as more Stern Gang than Weather Underground, with visions of potential King David Hotels chockablock with anti-Semites swirling in his head like sugar plums. And, as often happens, the left fought “the establishment” to separate themselves from it, while the right fought the establishment to become part of it and assimilate it. And the right, in this case as in many others, usually had the better strategy.

And there is another tradition, one almost entirely ignored by Magid, that provides a much more important ideological context for Kahane than either the Panthers or the Jewish left; namely, the long history of racialized violence (and threats of such violence) against racial minorities. I found no mention of George Wallace in the book, despite the fact that in October 1968, as part of his third-party presidential bid, he filled Madison Square Garden. Wallace, however, when conjuring images of violence against his enemies, was not drawing from the Black Panther playbook. Wallace’s success in New York City was one example of the growing firestorm of racial resentments that was roiling New York City during these years, especially in Kahane’s prime bailiwick, the outer boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, from the somewhat nebulous organization, SPONGE (Society for the Prevention of Negroes Getting Everything) to Mario Procaccino, the 1969 Democratic candidate for mayor, whose lasting contribution to the English language was coining the phrase “limousine liberal.” It’s not as if Kahane had to do much inciting to get a following. When, in the early 1970s, a potential housing project in Forest Hills (a middle-class neighborhood in Queens) engendered intense resistance, Kahane professed to be surprised at their virulence. “Suddenly all these Jews that used to get up in the Forest Hills Jewish Center and says the JDL uses violence and that they’re bad, come up to me and say, ‘Listen, if that housing project goes up, can you blow it up?” But Kahane said no. When the JDL marched down Fifth Avenue in the annual “Salute to Israel” parade, few groups were applauded more vigorously, or received more donations.

When it came to confronting Blacks, many Jews felt they suffered from a reputation of being insufficiently “tough.” In its early years, the JDL, not surprisingly, found many recruits in Kahane’s home base of Rochdale. I had many friends and acquaintances in Kahane’s orbit, and they all gave me the same recruiting talk, “Aren’t you tired of being pushed around by tough Blacks? Isn’t it time we Jews learned how to defend ourselves?” By that time, I was already in Hashomer Hatzair, and had nothing but disdain for the JDL and Kahane, but as an archetype of Jewish pusillanimity—unathletic, non-confrontational, very nearsighted, and very bookish—I certainly understood the JDL’s invoking an assertive brand of Jewish masculinity that I both abhorred and, on some level, envied. And for every teenage member of Kahane’s shock troops, there were ten, if not a hundred, quiet admirers.

I would argue that the appeal of the JDL, in Rochdale and elsewhere, was less about crime (or “Black crime”) itself, but a desire to defend one’s turf against encroachment, the Jets against the Sharks. A key part of the appeal, at a time of rampant “neighborhood change,” was the belief that sufficient Jewish toughness could stay the sociological and demographic forces of the day. Kahane was an outer borough Jew who repeatedly mocked the assimilated Jews from “Scarsdale” and “Great Neck,” who had presumably given up the fight to preserve Jewish communities in the city, and he lauded the Jews who had remained in the outer boroughs. Kahane had been a rabbi in Laurelton, another community in Southeastern Queens. But Laurelton was “changing.” More and more Jewish families were leaving; more and more Black families were moving in. Something very similar would follow in Rochdale. And the Jews in those neighborhoods and many others would fight fiercely, though fruitlessly, to preserve their white and Jewish character. The war to maintain Laurelton and Rochdale as Jewish neighborhoods were wars the Jews lost. There would be no six-day victory. And I believe that on some level that when Kahane moved to Israel he saw the Palestinians less as terrorists than as unwanted neighbors who would move in and force the Jews out. Israel was Laurelton and Rochdale. The West Bank was the rest of South Jamaica.

Others, I would suggest, also saw the world from the vantage point of southeastern Queens writ large. A short bus ride away from Rochdale, those living in Jamacia Estates, an exclusive subdivision for the upper middle class and beyond, could also observe the rising tide of Blackness just outside of their enclave, including a young Donald Trump. I make no claim that Kahane influenced Trump, but Trump surely knew of him as the leading local voice of racial resentment. The two men shared the same bleak worldview; if you give “them” [Blacks, Palestinians, immigrants, any “them” will do] an inch they will take a mile. If we are strident enough, outrageous enough, they will not replace us. Make of that what you will.

One final story. One reason I know so much about Rochdale is not only that I lived there, but about a decade ago, I wrote a book about it, published by Cornell University Press, telling how Jews and Blacks created an integrated community there, and how it fell apart. I interviewed a lot of people for the book, from associates of Robert Moses to fire-breathing Black revolutionaries; anyone who could help tell the story of Rochdale. I wanted to interview Kahane’s widow, Libby, a librarian at Hebrew University, and I managed to get her contact information. She proved to be very helpful and interested in my project, and at one point in our emails, she sent me an unpublished manuscript of her biography of Kahane. I was very impressed. It was, not surprisingly, sympathetic to his politics, but it was not a diatribe. It was well-written, carefully documented, and she had interviewed many of his cronies, who presumably wouldn’t have spoken to many other interviewers. I was impressed and told her that in one of my emails. (Magid is also impressed by Libby Kahane’s research). Anyway, a few years later, Libby contacted me. The book was being printed in Jerusalem by the Institute for the Publication of the Writings of Meir Kahane, and she wanted to use an excerpt from one of the emails as a blurb for the book. I blanched, but the quote she chose wasn’t really embarrassing, something like “an important and thorough study of one of the most controversial Jewish figures of our time.” And Libby had given me solid help, and I felt I needed to return the favor. And so I did. I don’t know what the moral of this story is, other than the fact that Meir Kahane, in life and death, is still with us, and those who wish to simply dismiss him as an inconsequential rabble-rouser, do so at their own peril. Shaul Magid’s book is not the last word on Meir Kahane, but it doesn’t have to be. Those interested in the vicissitudes of American Jewish life from the 1960s through 1980s, and its lingering reverberations in the US and Israel, should read this book.

___

Peter Eisenstadt is a member of the board of Partners for Progressive Israel and the author of Against the Hounds of Hell: A Biography of Howard Thurman (University of Virginia, 2021).

I think radical is too gracious a word to describe Kahane. As radical thinking can go in either direction, to help humankind or hinder. Racist,, troubled soul and perhaps fascistic in his behaviors is more appropriate.