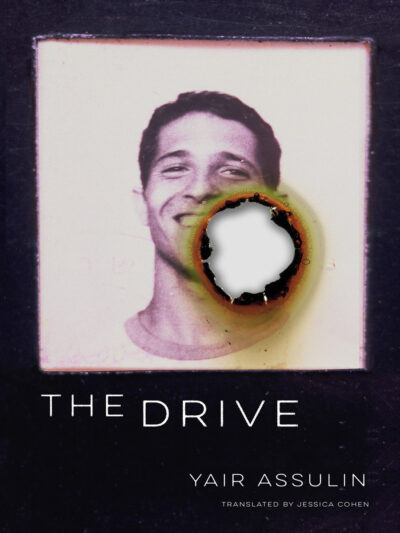

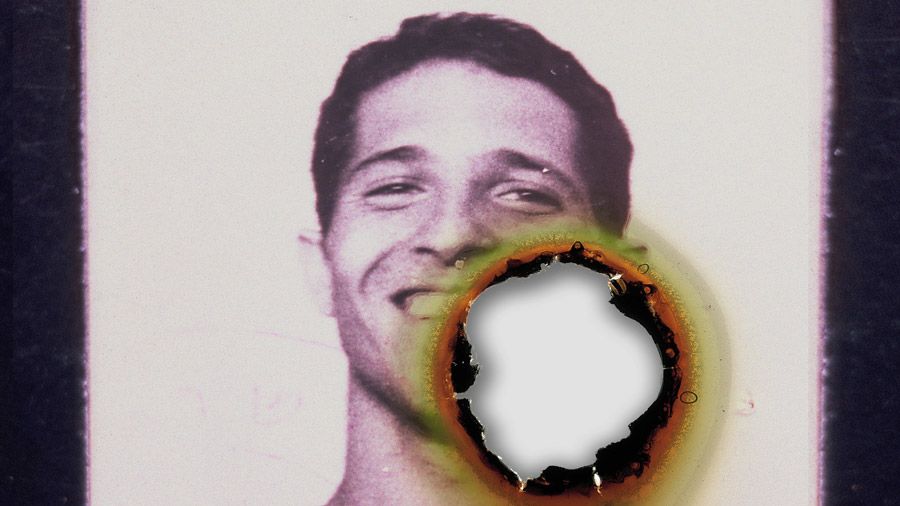

The Self as the Soul of the Nation: A Review of Yair Assulin’s The Drive

By Julie Arden Ficks

Yair Assulin opens his evocative 2020 novel, The Drive, with two quotes: “In the army, they don’t teach you how to kill; they teach you how to get killed,” by Israeli filmmaker Yehuda Judd Ne’eman; and “It is my political right to be a subject which I must protect,” by French philosopher Roland Barthes. Already infused into its pages is the dichotomy between the larger, societal mechanism (the army), and the individual (the subject). In The Drive, Assulin explores the relationship between the army and the subject, or the self, in a way that has rarely been seen before in Israeli literature.

“‘To be a subject.’ [Barthes]. This is in, a lot of ways, the deep essence of my novel,” Assulin stated at an interview organized by his American publisher, New Vessel Press, in 2020. First published in Hebrew in 2011, the novel tells the story of a young man who struggles immensely to fulfill his Israeli army service. It is written in first-person and consists of short, story-like chapters. It is set inside of a car, as the narrator’s father drives him to the Mental Health Officer (MHO) at Tel Hashomer Hospital. During the car ride, the narrator describes how he ends up pursuing a mental health exemption from army service—one of the most shameful paths one can go down in Israeli society.

He describes his experience in the army as being “suffocated,” and that when he began his service, he realized that he was committed to “three years of slow death” (Assulin 20). Whenever he expresses his difficulty being in the army to his family, friends and fellow soldiers, not one person is able to console him. This is because the army is a fact of life; so deeply ingrained in the fabric of Israeli society, it is something everyone either must go through, or has already gone through. If everyone goes through it and manages, how bad can it really be?

He describes his experience in the army as being “suffocated,” and that when he began his service, he realized that he was committed to “three years of slow death” (Assulin 20). Whenever he expresses his difficulty being in the army to his family, friends and fellow soldiers, not one person is able to console him. This is because the army is a fact of life; so deeply ingrained in the fabric of Israeli society, it is something everyone either must go through, or has already gone through. If everyone goes through it and manages, how bad can it really be?

The narrator becomes depressed and frequently contemplates suicide. At one point, he begs one of his friends to slam his hand in a car door in order to get longer time off.

This is not a novel of complex politics. It is an effective account of how being in the Israeli army impacts mental health. Some readers may be disappointed by the lack of detail and repetitive nature of the book, which are valid criticisms. However, the omission of certain details can be seen as purposeful. Instead of analyzing the workings of Israeli army and the roles of its soldiers more acutely, the novel explores how the mere fact of having to serve in the army—considered the most important service to the nation—emotionally influences the individual.

It is not to say that these themes are mutually exclusive. Perhaps if the novel delved any deeper into a political stance, it would alienate readers. Despite questioning the obligation to serve in the army and arguing that this path is not for everyone, the book received generally positive reviews from both the left and right in Israel, winning the Sapir and Israeli Ministry of Culture prizes.

The true breakthrough this novel created might be more difficult to recognize by an American audience, however. In an online interview with The Drive’s editor at New Vessel Press, Israeli writer Rubi Namdar noted that the novel marks “the beginning of a new era in Israeli culture.” This is because although the narrator is Mizrahi and religious, the narrative is primarily concerned with his identity as an Israeli; about collective experience rather than individual.

The narrator’s experience also stands far from the typical narrative of the wartime hero and traditional masculinity. Discussing mental health issues, particularly depression and suicide, remain taboo to acknowledge and talk about openly—with oneself and also with family members. This is doubly true given the fact that the narrator is a man. It becomes clear that in the IDF, individuals frequently attempt to use mental health issues as a way to evade army service. People who are actually suffering are oftentimes not taken seriously because of this.

The narrator’s behavior makes both of his parents, his significant other, the army officials, and the reader wonder if he is being abused. His answer is no. This is perhaps the most surprising and illuminating aspect of the novel: one does not need to be in an extreme circumstance in order to reject army service—feeling that one does not belong is enough. Some readers may contend that this makes the narrator weak and self-centered, but to others, he is a hero.

“I don’t really know how to explain what went wrong or how, but I just know that I can’t tolerate the situation there. My soul can’t tolerate it,” (Assulin 107) the narrator explains to the Mental Health Officer. After repeatedly telling those around him this and constantly being told that his concerns are unfounded, he is sure of this statement, echoing the experiences, fears and feelings of many in the army today and before him.

———-

Julie Arden Ficks is the Program Coordinator at Partners for Progressive Israel. She holds a B.A. in Literature and an M.A. in English and will be pursuing a J.D. at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University this fall, focusing on Women, Gender & the Law.

Leave A Comment