I don’t care what they say, I love, and loved, the 1964–65 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, Queens. This week is its 50th anniversary, and as usual the nay-sayers are in the saddle. A series of articles in the Times alleges that the fair was derivative and uninspired, it couldn’t hold a candle to the 1939-40 World’s Fair, left no legacy, helped make the whole notion of a “world’s fair” obsolete, was a simple-minded celebration of capitalist excess and one final exhibition of Robert Moses’s megalomania before his long overdue superannuation.

I don’t care what they say, I love, and loved, the 1964–65 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, Queens. This week is its 50th anniversary, and as usual the nay-sayers are in the saddle. A series of articles in the Times alleges that the fair was derivative and uninspired, it couldn’t hold a candle to the 1939-40 World’s Fair, left no legacy, helped make the whole notion of a “world’s fair” obsolete, was a simple-minded celebration of capitalist excess and one final exhibition of Robert Moses’s megalomania before his long overdue superannuation. I don’t buy any of it, or at least, I don’t care. When I was ten years old, and living in Queens, the World’s Fair was a magical place. I don’t know how many times I went there—about 15, I suspect. It was inexpensive and always endlessly entertaining. I was minus 15 years old in 1939, so I never got to the earlier fair, and I was in no position to make invidious comparisons. I loved the fair I had.

What are my memories? All of those rides in the IBM and GM pavilions, with their radically off-target views of the future. Those animatronic computers, singing “It’s a small world, after all,” or the animatronic Lincoln in the Illinois pavilion. The Continental Insurance Company’s wonderful exhibit about the Revolutionary War. The panorama of New York City (which is still there, and still worth a visit to the Queens Museum. The now badly decayed map of New York State, the size of a football field. My outrage at being charged a whole quarter for a slice of pizza, well above the just price of 15 cents.

|

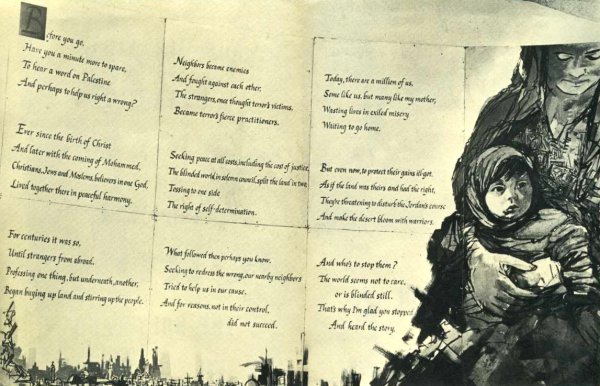

| Jordanian pavilion mural, ’64 World’s Fair |

What I do not remember are any of the international pavilions, except for the Vatican pavilion, with Michelangelo’s Pieta, and for some reason, the Philippines pavilion, plastered with large pictures of Ferdinand Marcos, then at the beginning of his odious reign. I must have gone to the Israel pavilion, but have no memory of it. I don’t know if I went to the Jordanian pavilion. Thereby hangs a tale, one I became acquainted with many years later, as part of research on a different project.

When the Jordanian pavilion opened, to the dismay of many, it contained a mural dedicated to the Palestinian refugees, dominated by a mother and her young son, insisting that the world “remember the Palestinian refugees.” Admittedly, the text accompanying the mural was not entirely accurate. “Ever since the birth of Christ, and later with the coming of Mohammed, Christians, Jews, and Moslems believing in one God lived there is perfect harmony.” (I suppose there was no reason in angering Christians by bringing up the Crusades, or the less than ideal treatment of Jews over the centuries under Muslim or Ottoman rule.) And the account of the history of Zionism was certainly provocative. “Strangers from abroad began buying up land and stirring up the people. Today there a million of us, wasting our lives in exile and misery, waiting to go home.”

The reaction of the Jewish community in New York City to the mural was to condemn it as anti-Semitic “offensive and malicious propaganda,” wholly out of keeping with the spirit of the fair. Soon every major politician in the city, from Mayor Wagner on down, was insisting that the mural be removed. Suits were filed. Protesters from the American Jewish Congress, inspired by Martin Luther King, engaged in protests and civil disobedience, and were arrested by policemen at the fair.

As for Robert Moses, he wasn’t having any of it. He was not in the habit of being told by others what to do, and a lifelong antipathy to Zionism and rejection of any Jewish identity (hardly uncommon for persons from his upper class German-Jewish milieu) gave him very little sympathy with the protestors. (The only Jewish organization he had any connection to was the vehemently anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism.) And had he listened to the protestors, no doubt every pavilion from an Islamic country would have left, and he would have had a bigger problem on his hands. So Moses stood his ground. The protests ebbed. The Jordanian mural was not removed. Moses later complained of “a burst of simulated indignation by pro-Israeli groups,” and the efforts of “fanatics” and “professional religionists” to disrupt the fair, the incident proving only “that there were no Arab votes in New York.” (For his efforts, King Hussein awarded Moses the Star of Jordan Decoration of the First Order in 1965.)

What can we learn from this incident? It is often said that relations between Israel and Palestine are worse than they ever were, and, with the apparent scuttling of the Kerry negotiations, it has been a field day for pessimists. Perhaps they are right, but in at least one way, the mutual understanding between Israelis and American Jews and Palestinians has definitely improved. In 1964, American Jews, and very liberal American Jews at that, simply could not listen to any claim by the Palestinian refugees. Any attack on Israel was simply an instance of anti-Semitism. There was no general recognition that, as we now say, there are two “narratives,” two histories, two more or less equally valid ways of looking at the same set of tragic events.

The leader of the American Jewish Congress’s protests at the World’s Fair was Reform Rabbi Joachim Prinz, a refugee from Germany, long one of my heroes, a stalwart supporter of civil rights and many other good causes in his many decades in America. Among those arrested at the fair was Theodore Bikel, who still, in his 90s, is a leading voice for Israeli-Palestinian understanding and reconciliation. The basic legitimacy of the Palestinian refugee’s cause is now an article of faith among liberal and progressive Jews. (How to solve it is another matter altogether.) And even moderate and many conservative Jews acknowledge that without some attention to legitimate Palestinian grievances, dating from 1948 on, there will be no lasting solution of the problem. And most Palestinians recognize that Israel is not going anywhere, and cannot be wished or wiped away. This is of course an all too common occurrence in the history of politics between peoples. An understanding of the conflict that would have been of great use, at an earlier point in time, comes too late, and is too delayed, to be of any use, because the conflict has moved on. If only Netanyahu and Abbas, or their predecessors half a century ago, could have tried to negotiate their differences in 1964, instead of waiting until 2014!

And what of Robert Moses? He had an op-ed in the Times in 1971, “Harness the Jordan,” in which he suggested, as was his wont, the Israeli-Palestinian problem could be solved through building things, in this case, damming the Jordan River and releasing its full hydroelectric capacity. Rather than the current situation—“conflicting claims of race, religion and government. Both Israelis and Arabs are raking old ashes, stirring smoldering fires and fanning fanaticism. Each side refuses to yield an inch”—Moses wanted negotiations. Moses concluded that “obviously Israel must give back some of the land recently acquired, but should have viable frontiers.” Other than the one word, “recently,” Moses’s comments remain as apposite today as in 1971. Moses understood that the reason to acquire power was not to hoard it, but to use it, and use it to make a deal. Netanyahu could learn a lesson from the power broker.

Thanks for your great memories of the Flushing Worlds Fair. I was also living in Queens then, a few years older and my first job was selling cokes and ice cream (for 25 cents!) at the Florida Water Ski Pavilion. So I was there almost every day during the summer of 1965 and loved it.

Interestingly I have absolutely no memory of the Jordanian controversy you write about. Israel wasn’t big on my radar screen then but I think I would have heard about it. Anyway, your comments are right on point, and I think, in this season of disappointment and continually lowered expectations, it’s worth remembering how absolutely incomprehensible the Arab and Jewish sides were to each other at that time.

Paul Scham

Thanks for the memories. It was my first tourist trip to New York, and I got Rod Serling’s autograph on a napkin in a hotel coffee shop, which I promptly lost. I was 12.

Yes, things have changed and will continue to change. In twenty years Jewish liberals (those that remain) will realize, with sadness, that the Oslo Accords were a honey-trap for the Palestinians, that the Palestinian Authority was the great enabler of the Occupation, and that BDS was the only way to save Israel from itself. Perhaps by then, opinion makers like Friedman, Remnick, and Goldberg will be replaced by Americans with names like Barghouti, Khalidi, and Nusseibeh, and a fading imperial giant like the US will lack the creds with both sides.

It’s a nice dream, anyway

Read this over again. Really interesting. I love the role of Bikel. That does say a lot. But — and I think here of Avi Shavit’s claim that Israel has moved to the left in the last two decades and that Netanyahu is way to the left of Rabin on the question of Palestinian statehood — I don’t think what the principal players — the US, Israel gov’s — DO is much different, nor has the situation of the Palestinians on the ground significantly improved, except what you would imagine as standards of living go up internationally. It’s as if you had the Republicans honoring ML King, as they now do, and Southern capitals taking down the Confederate flag, but racial segregation enduring as if Brown v. Board and the Civil Rights Acts had never existed. This auhtor is right about changes overall in American Jewish attitudes, and the same could be said of the Europeans, and that, along with the creation of some kind of Palestinian entity and official leadership, has forced the Israelis to change their rhetorical stance on two states and Palestinian rights. But I think in some sense the Israeli government is as rightwing as ever and that their policies, what they do, are aimed at annexation — something that Rabin did not favor in 1993…. John Judis