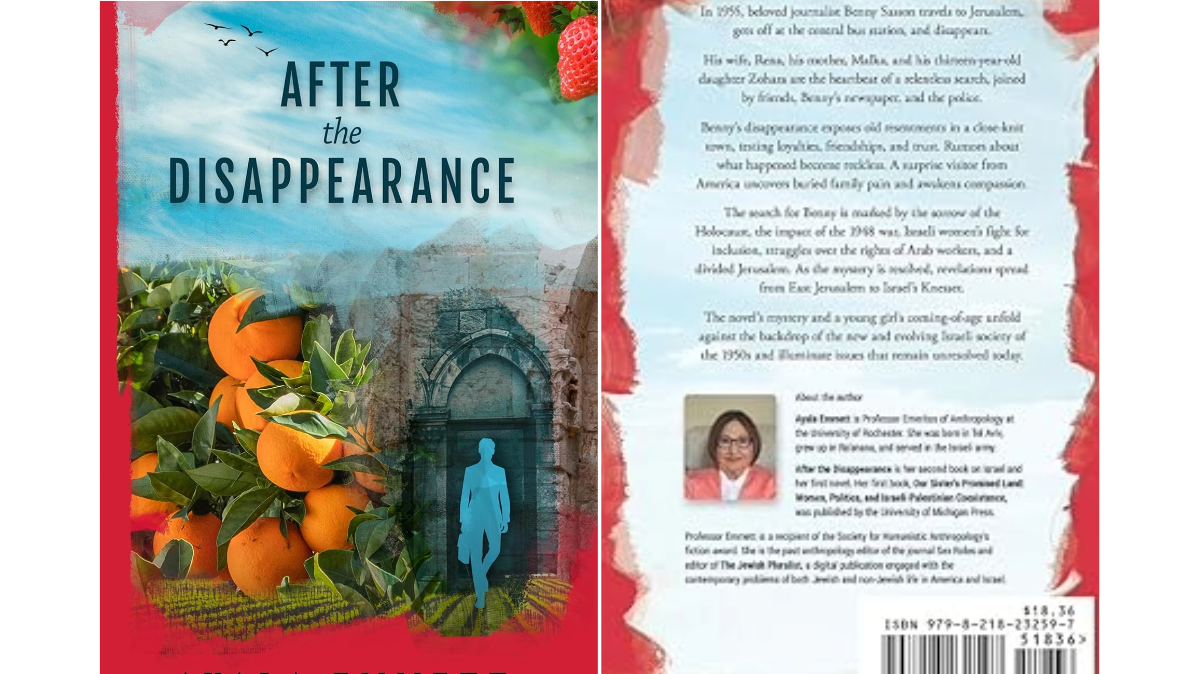

Ayala Emmet, After the Disappearance (2023), review and interview with the author

By Peter Eisenstadt

Benny Sasson was missing. His mother Malka, wife Rena, and thirteen-year old daughter, Zohara, were frantic with worry. One day in 1955, Benny took the bus from his home town of Shomriya (a fictional town in central Israel) for his usual commute to his office in Tel Aviv, where he was a journalist at a left of center newspaper. He arrived in his office, but around midday he left for Jerusalem, where his itinerary included dinner plans with a somewhat shady member of Knesset. People saw him get off the bus at Jerusalem’s Central Bus Station, but he never arrived for his dinner engagement. The police were called, and investigated, but they were baffled. Benny could not be found. Days became weeks, weeks became months.

Some Shomriya neighbors were extremely supportive, but the town gossips shared dark suspicions. Israel, in 1955, was a small country—about the size of New Jersey, the gazetteers used to say—and people just didn’t vanish in Israel in the 1950s. Perhaps he had fled the country because he was in the intelligence service of a foreign power, and, given his politics, some thought the Soviet Union was his most likely destination. And then…well, sorry, this is where the reviewer’s code of omerta kicks in. If you want to find out what happened to Benny, you will have to read Ayala Emmett’s excellent new novel, After the Disappearance. And I urge you to do so. It is available on Amazon as a paperback and an e-book.

After the Disappearance, is, in terms of its genre, a mystery and a police procedural, and a good one. It is a taut and exciting missing person’s case, with good cops and bad cops, purloined documents, plot twists, and, of course, a murder. There is also a McGuffin: Benny was working on a controversial article on the inequities faced by Palestinian labor in Israel and finishing a book MS on the political and religious significance of Martin Buber’s quest for a binational state throughout the book. But the novel is as much “about” its context—Israel in the 1950s—as it is about its plot. And the novel’s depiction of Israel, as viewed through the lives of its characters, is powerful, perceptive, and often, quite moving.

Before proceeding, I should acknowledge that Ayala is a dear friend—I will call her Ayala rather than Emmett in this review, if that’s okay with you—and she is a member of the board of Partners for Progressive Israel, the organization that publishes Israel Horizons. So yeah, seldom will be heard a disparaging word in this review. Nonetheless, I stoutly insist that this is a book worth reading.

This is Ayala’s first novel, but it is the product of a lifetime’s thoughtful pondering of the fate of Israel, and it is not her first book about Israel. That was Our Sisters’ Promised Land: Women, Politics, and Israeli-Palestinian Coexistence (2003), which you should also read. Ayala is an emerita professor of anthropology at the University of Rochester, and brings to After the Disappearance an anthropologist’s eye and sensitivity to the telling detail (such as the fact that most middle class families in Israel in the mid-1950s did not have private telephone service at home.)

The book’s prose is lyrical and precise; the scene setting is often exquisite, and both the main character and a host of minor characters are finely rendered. Benny Sasson’s late father was from an old Sephardic family from Jerusalem. His mother, Malka, was born in Odessa and came to Palestine during the Second Aliyah, and is a dedicated farmer and ex-kibbutznik. Rena, an artist, emigrated from Poland in the mid-1930s, and lost all of her family except for her brother, Joe, who left for the United States at about the same time. Benny’s disappearance led Joe to visit Israel for the first time. Brother and sister, not close physically or emotionally, had not seen each other for 20 years. Zohara’s best friend, Shoshi Abarbanel is from a religious Sephardi family, and the crisis of Benny’s disappearance led Zohara to interact with Judaism and God in deeper ways than the conventional secular Zionism of her parents. Mendel, a font of avuncular wisdom, owns a café in the center of town that is a frequent meeting place for all of the novel’s main characters, next door to the book store. (Like Jews everywhere, eating and reading are activities of primary importance for Shomriya residents.) For all that, my favorite minor character in the novel is Vashti the donkey, who brays loudly throughout.

Ayala was born in Tel Aviv in 1935, and raised in Ra’anana, about 20 kilometers northeast of Tel Aviv. After the Disappearance is not autobiographical, but the fictional town of Shomriya is based on Ayala’s memories of her hometown, and many of the people in the novel are drawn from people and types of persons she remembers. Ayala told me that she wanted the novel to be “ethnographic in the sense that most of it is culturally accurate. In other words, the characters are fictional, but the way they speak and think and interact and function is accurate to the time and place and people.” Ra’anana had a population of 615 according to a 1931 census, a population of several thousand during Ayala’s childhood, and today is a city of some 80,000 residents. During her early years Ra’anana was a town of diversities, different communities of working class and bourgeois Orthodox Jews, with three kinds of schools, “one for leftist workers, one for the Orthodox, and one for the political center.” Ra’anana had one synagogue when she was growing up, now it has nearly 100. It was a town which was making the transition from a largely agricultural community—her childhood home had enough space for some chickens, a cow, and some goats—to an industrial city. Ayala’s family was socialist in their politics, and Orthodox in their Judaism, and her parents were devoted Halutzim, dedicated to “redeeming the land.”

Ayala has clear memories of independence in 1948. “Certainly Ra’anana was engulfed in emotion; amazement, and I think some fear, too. We looked at each other, even the children, and there was the sense that we were changing history. We made this after 2,000 years. We finally are safe. That was the big thing. Now that we have a Jewish homeland, there will be no more killings, no more persecutions, and no more expulsions. By then of course we already had waves of refugees. But we were silent about the Holocaust. We wouldn’t let it happen to us. There was a physical love for the land and a overwhelming yearning for safety…We did it. We did it!”

Ayala also has other memories of 1948. “There were two Arab villages nearby. Before 1947 we had pretty good relationships with the village of Khirbet Azzun; they would come into town to sell produce and I remember seeing them. I remember very well when they disappeared. I remember standing there and seeing them leaving. I remember being very confused. My parents said nothing about it. Maybe the adults talked among themselves, but to the children they said absolutely nothing. No one talked to us about it. No one said why they weren’t there anymore, and very soon after they left, tractors came and kind of demolished the remains of the village. We grew up with two big secrets: the silence about the Holocaust, and the silence of what was happening all around us. We grew up being taught not to see things. So it was easy after 1967 not to see the tragedy/injustice of the occupation.”

After the Disappearance takes us to a largely forgotten time , the Israel of the 1950s. Ayala set the novel in 1955, a year of relative quiet, a year in which Moshe Sharett, whom she admires, was prime minister, as opposed to the more militaristic David Ben-Gurion. The year 1955 was a year when “external politics didn’t crash or obliterate daily life. And I’m interested in daily life, you know, as an anthropologist. This is where you discover things.” It is not a political or a didactic novel, or rather, it is a novel of small politics rather than big politics; family politics, office politics, neighborhood politics, the politics of people more concerned with their own lives than with impinging questions of state, until, they are forced by circumstances to pay heed to them.

In many ways, the 1950s is a unique decade in Israel’s history, sandwiched between the radical newness of 1948 and the distended, engorged Israel that has existed since 1967. (Ayala remembers liking Jerusalem more before 1967 than afterwards. “It was a safe place, a comfortable place. We felt at home there. We felt we belonged there. We looked at the Jordanian soldiers but felt absolutely no threat whatsoever. None. And for those of us who weren’t particularly attached to the Kotel, it meant nothing to us. It’s not like we didn’t have Jerusalem. We had Jerusalem. It’s no longer peaceful, it’s divisive, it’s oppressive.”) Both East and West Jerusalem play important parts in the novel.

The 1950s was a decade of consolidation, not transformation. Israel was a more complacent place, perhaps the last decade in which the old Zionist verities were largely unchallenged and unchallengeable. It was a decade of assimilation and a coerced effort to eliminate differences, whether it was previous experiences in Europe or the Middle East, or previous languages, like Yiddish or Ladino. It was a decade of disappearances, silences, and absences, things that you knew that you were expected not to talk to about. Mizrachi newcomers were relegated to out-of- the-way and generally miserable settlement towns. Holocaust survivors were pitied as damaged goods, usually ignored, and expected to keep their personal tragedies to themselves, and even those mourning the death of Israeli soldiers in the 1948 war found their private needs unaddressed and unattended.

But the most important topic of non-conversation was the Palestinians, whether it was the disappeared Palestinians and their abandoned communities, or the Palestinians who remained. As Benny’s article on Arab labor would have no doubt pointed out, Israeli Palestinians were under military administrative rule throughout the decade, enforcing their marginality and invisibility, and it was not employment opportunities but the military who usually determined where, how, and for whom Palestinians could work.. Grief was a private, unhelpful emotion; all emotional energies were to be channeled into the building of the new state. Individuality was less important than fitting in, and those who couldn’t, or wouldn’t, fit in were simply ignored.

The emotional need to be accepted, to be in the in-group, is perhaps at its height among teenage girls and boys. Israel was a teenage country in the 1950s. This is perhaps why Ayala placed Zohara, a thirteen year-old girl, at the fulcrum of the novel. According to Ayala, “Zohara didn’t like the idea that that her parents were leftist; she wanted to be like all the other kids. She was a good kid, but also didn’t want to hear about or think about what her father was writing about the Arabs who left. It’s hard for me to describe the silence, and I wanted so to be a good kid then.”

How would the Israel of the 1950s have evolved without the Six Day War? Would Israel, over time, have been able to address its silences and democratic limitations better than it has, without the forever unhealed wound of the occupation? Perhaps, though of course we will never know. Ayala wrote her novel “to shine the light on what we don’t want to talk about.” The issues that Israeli and American Jews do not want to talk about have both evolved and remained the same. Ayala has spent a lifetime trying to speak about those silences. Perhaps the events of the past year have finally exploded whatever remains of the lingering Zionist consensus of the 1950s, though whether for good or ill is as yet unclear. The forces pulling Israel apart now seem to be stronger than those holding it together. Israel is now in an unprecedent crisis, facing a far right messianic, racist, misogynist government engulfed by protesters defending the Declaration of Independence and fighting for its promise of democracy. And perhaps that is why, at a time when it is so easy for many of us to abhor and detest the actions of the government of Israel, After the Disappearance is so worth reading. Its Israel was not a simpler time, but it was a quieter time. What was not spoken about in Ayala’s novel is now shouted on rooftops, blared over the internet, chanted in the central squares of Tel Aviv, blocking the Ayalon Highway, fought over in the West Bank, in Jerusalem, in the Knesset, everywhere.

Zohara’s favorite novel, which she reads intermittently as events unfold, is a Hebrew language translation of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Ayala probably did not intend this as a political commentary, but consider poor Israel; Lilliputian then, now Brobdingnagian and governed by the Yahoos. Let us hope the Yahoos do not prevail. Ayala’s novel is at once a love letter to Israel, its land and its people, and an expression of her deep fears and distress at what 1950s Israel has become.

___

Peter Eisenstadt is a member of the board of Partners for Progressive Israel and the author of Against the Hounds of Hell: A Biography of Howard Thurman (University of Virginia, 2021).

Leave A Comment