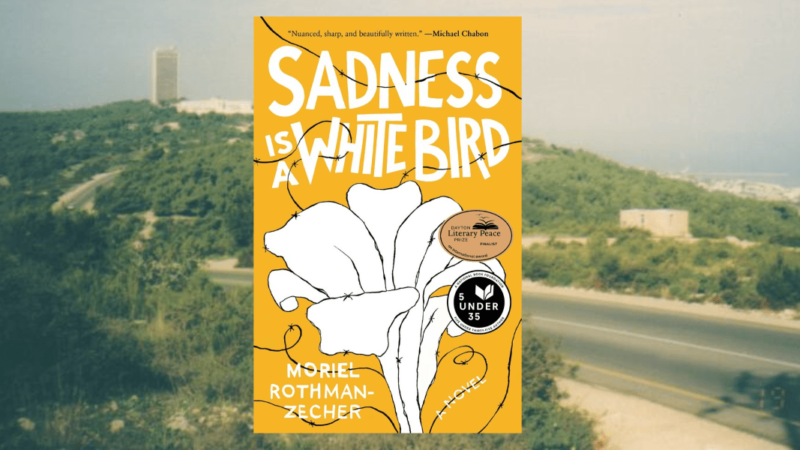

Olive Branch Dreams: A Review of Moriel Rothman-Zecher’s Sadness is a White Bird

(Atria Books, 2019)

What kinds of relationships are possible, lasting – between Israeli Jews and Palestinians? What kinds of circumstances will break these relationships apart; what is needed to make them last? These are the questions that Moriel Rothmen-Zecher in his debut coming-of-age novel, Sadness is a White Bird, seeks to answer.

The book’s title comes from the English translation of Mahmoud Darwish’s 1967 poem “A Soldier Dreams of White Lilies.” It is a poem that the main characters of the novel – Israeli and Palestinian – share with one another. The poem tells a story of compassion for the “other” through a dialogue between the speaker, a Palestinian, and an Israeli soldier. The solider described by the Palestinian in the poem does not dream of death or destruction: “he dreams of white lilies / of an olive branch… sadness is a white bird that does not come / near a battlefield.” Embedded with Palestinian symbols of peace, the poem explores sympathy and common ground between both peoples who become adversaries not because they want to, but because they are forced to by external circumstances.

The novel begins in “the florescent glow” of an Israeli army jail cell with nineteen-year-old Jonathan. In first-person, he tenderly narrates to a boy named Laith while the reader is left to wonder how he got there. It is unclear whether Jonathan is speaking to Laith in real time, imagining this epistle in his head, perhaps writing him a letter or speaking to the dead.

Jonathan recounts the events leading up to his imprisonment and moments in his past that define his identity. Israeli-born but raised in Pennsylvania, his family moves back to Israel due to his grandfather’s cancer diagnosis. While awaiting his Israel Defense Forces draft date, Jonathan unexpectedly meets Palestinian twins Nimreen and Laith, students at Haifa University – and their lives are forever changed.

The three grow incredibly close, traveling together, hitchhiking from Ein Tzvi, wandering along Masada Street in Haifa and sharing their most personal thoughts. The yearning with which Jonathan talks about Laith and Nimreen eventually unfolds as a romance. His male gaze that initially comes across as grating turns into a queer one: his sexual and emotional relationship with Nimreen becomes intertwined with his equally deep but largely unconsummated love for Laith. Although Jonathan’s queerness is, at times, undeveloped, his fluidity symbolizes that love is a way to repair the conflict – love for all people regardless of gender, faith, race, or history.

Trying to help one another understand, Jonathan, Nimreen and Laith reveal intergenerational traumas related to their heritage and land and religion. Jonathan assures his friends that for his grandfather, a Salconian Jew who escaped the Nazis and arrived at the port of Haifa in the early 1930s, “zionism wasn’t about greed or getting rich. It was about survival. Without Zionism, I probably wouldn’t be alive.” Jonathan meets the twins’ grandmother who tells him about her tragic experience being at the Qfar Qasim massacre.

Through storytelling, friendship and romance, Jonathan begins seeing the realities of the occupation from the perspective of his friends. As someone who morally rejects the occupation yet strongly believes in the existence of the Jewish state, his decision to join the IDF becomes increasingly complicated.

Lyrical and honest, Sadness is a White Bird offers hope for the reshaping of Israeli-Arab and Israeli-Palestinian relations; a heartbreaking story of radical love, friendship, politics, and the barriers between them.

———

Julie Arden Ficks is the Program Coordinator at Partners for Progressive Israel. She is also a recent M.A. English graduate with specializations in Contemporary Literature, Gender and Sexuality Studies and Literacy.

Leave A Comment