The Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia began with the annexation of the largely German-speaking Sudetenland in October 1938. Rendered impotent by the loss of its heavily-fortified defensive line along the old border, all of Czechoslovakia surrendered without firing a shot when Hitler completed his conquest in March 1939.

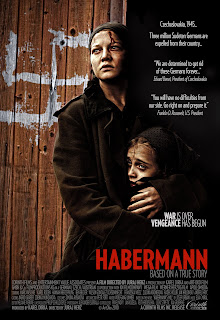

Most people are unaware of the aftermath of this occupation, when the Czech people took revenge on their German-speaking neighbors. This story is explored in a German-Czech-Austrian feature film co-production, Habermann.

The film’s press packet points out that three million German-speaking Czech citizens were violently pushed into Germany and Austria after the war. The film’s poster quotes Czechoslovakia’s President Eduard Benes on getting “rid of these Germans forever” and Franklin Roosevelt’s concurrence. 270,000 Czechoslovakian Germans were “unaccounted for” — most probably murdered.

Yet, since most of the film depicts the Nazi occupation and instances of local German collaboration with the Nazis, Habermann should not be taken as an unseemly exercise in revisionist exculpation of the Germans. Rather, it mostly treats its characters as morally complex individuals. For example, we see how a Czech hotel manager maneuvers between the Nazis and the resistance to survive and prosper.

Supporters of the Palestinian cause might note that upwards of ten million ethnic Germans fled and were evicted from Czechoslovakia, Poland, the Baltic states and other parts of Eastern Europe, with no prospect for return or compensation. The East Prussian city of Königsberg (birthplace of the famous German philosopher Immanuel Kant) became the Soviet-Russian city of Kaliningrad, while the German Baltic port of Danzig and the Silesian city of Breslau became the Polish cities of Gdansk and Wroclaw. Like 750,000 Palestinian Arabs in 1948, most of these Germans were innocent in the sense that non-combatants generally are, caught up in a ferocious war, which “their side” had started and ultimately lost.

In both cases, a total victory for their side would have meant a humanitarian calamity. This observation is obvious regarding the Nazis in World War II, but also likely if there had been an Arab victory in the war of 1948, during which the slaughter of Jews would have been in the many thousands, if not higher. As it was, even with the victory of the Jewish side in ’48, the Palestinian Jewish community suffered 6,000 killed and about 15,000 wounded, or 3.5 percent of its total population; and all Jews were ethnically cleansed (in a combination of massacre and expulsion) from the Old City of Jerusalem and the Etzion Bloc of settlements near Bethlehem, where Arab forces triumphed.

Germany absorbed its ethnic kin, while most Arab countries kept the Palestinians apart in camps. This doesn’t mean that any of these expulsions were just, or that the victims shouldn’t have been compensated. Any reasonable and comprehensive solution to the Palestinian refugee problem would implement a package of compensation and the option of resettlement in the new Palestinian state or in a third country in line with the provisions detailed in the Geneva Accord of 2003.

The ethnic German refugee millions never received an international aid agreement. That they were able to move on with their lives in a way that Palestinians have not, however, was very much to the Germans’ advantage. Still, Israel will likely never find peace until a sufficient accommodation is made with the Palestinians that allows them to also get on with their lives.

I’ve heard veteran Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat tell Jewish audiences that this should be addressed in part by an Israeli “apology” for Palestinian-Arab displacement. My feeling is that this would be very difficult because of the two peoples’ conflicting narratives; but if the Palestinians were also to admit that they and their Arab allies were wrong to have violently rejected the United Nations Partition Plan of 1947 and in attacking the Palestinian Jewish community in what became Israel’s War of Independence, then a certain reconciliation on an emotional level can be achieved. However, unless both sides are willing to acknowledge the full truth of 1947-48, which contravenes the limited self-serving understandings of both peoples, they’d all be better off leaving history to the historians.

P.S. For more details of the plot, see my review of Habermann in The Forward’s “Arty Semite” blog, which concludes with the film’s North American trailer. Coincidentally, a Czech film has just been released in the US at the same time; Protektor is overly artsy, but it also packs a wallop with its tale of the Nazi occupation of Prague and Czech reactions ranging from collaboration to resistance, and points in between. As with Habermann, the persecution of Jews is an important plot component.

As an aside, population displacement seems to follow or precede the emergence/re-emergence of nation-states. Vietnam, modern Turkey, India-Pakistan, the expulsion of Jews from Arab countries, and of course the gradual genocide/displacement of the First Nations in the Americas. War creates refugees as well, whether civil or non.

Which isn’t to say that populations expelled by nations, Israel included, were justified or correct in doing so. However, I’ve seen examples of people labeling the displacement of Palestinians as uniquely evil, or Israels ‘original sin’, which I find to be a touch irritating.

It should be noted that for 1947 partition plan, Irgun and Lehi rejected them too;ex, after the partition, Begin said:”the bisection of our homeland is illegal. It will never be recognized.”

Some Post-Zionist scholars endorse Simha Flapan’s view that it is a myth that Zionists accepted the partition as a compromise by which the Jewish community abandoned ambitions for the whole of Palestine and recognized the rights of the Arab Palestinians to their own state. Rather, Flapan argued, acceptance was only a tactical move that aimed to thwart the creation of an Arab Palestinian state and, concomitantly, expand the territory that had been assigned by the UN to the Jewish state

I’ve read Flapan and respect him. But I don’t think he wrote exactly what you state here.

He may have seen some cynicism in Ben-Gurion’s acceptance of partition, with B-G believing (correctly) that the Arabs would reject partition. If they had not done so, however, Palestine’s Arabs would have had a state.

And none of these so-called “post-Zionist” speculations account for the fact that B-G resisted the urgings of some of his commanders in late ’48 or early ’49 to continue the war in an effort to conquer all of Palestine. Nor does this notion account for B-G inveighing from retirement against Israel’s ongoing control of the West Bank and Gaza following their capture in 1967.

Thanks for feedback and I’ll re-read that portion. However, I found some quotes of Ben Gurion problematic:

“A partial Jewish State is not the end, but only the beginning. … I am certain that we well not be prevented from settling in the other parts of the country, either by mutual agreements with our Arab neighbors or by some other means. . . [If the Arabs refuse] we shall have to speak to them in another language. But we shall only have another language if we have a state.”

“The acceptance of partition does not commit us to renounce Transjordan: one does not demand from anybody to give up his vision. We shall accept a state in the boundaries fixed today, but the boundaries of Zionist aspirations are the concern of the Jewish people and no external factor will be able to limit them.”

“The debate has not been for or against the indivisibility of Eretz Israel. No Zionist can forgo the smallest portion of Eretz Israel. The Debate was over which of two routes would lead quicker to the common goal.”

You have to look at when B-G made such statements and to whom he was addressing them (because he was a politician). Some of these statements do not jive with actual positions he took at various times, as I’ve indicated to you earlier; they sound like something a right-wing Zionist would say — especially regarding Trans-Jordan.

[…] “refugees” to Israel are not clamoring to return Syrian refugees to Syria. After World War II, Germany resettled 12 million ethnic Germans expelled from Eastern Europe. Israel resettled most of […]